The Centrifugal Map

A Graphic Representation of Life on the Edge in the Great Age of Mediation

Just thought you might want to take a break from the manic ramblings everywhere else…

The following is excerpted directly from my 2012 book, The Media Addict’s Handbook: Restoring the Quality of Life in the Great Age of Mediation. But the Centrifugal Map was first imagined and described by yours truly way back in 1995, as one of three lifestyle tools I included in a failed book proposal about how the digital devices just then starting to migrate from the office into our homes would eventually erode the quality of our lives…

I remember childhood trips with my father to the Fun House at Playland at the Beach in San Francisco, now more than 55 years ago. I remember the carnival lights, sounds, smells, and flavors like they happened yesterday — still vivid and visceral. I remember the salt air, sharp and sweet, and how little scrap piles of kelp sometimes washed up on shore and glistened in the midday summer sun like an amber necklace along Ocean Beach. I remember the damp and piercing chill of the late afternoon fog as it rolled through, and the distant roar of the Pacific just across the asphalt ribbons of the Great Highway. I remember Laughing Sal, a female mechanical clown whose grotesque visage and cackling laugh presided over the entrance to the Fun House for decades. I remember how my father’s eyes widened when he saw her, and how his face brightened, the slumbering child inside him suddenly reawakened and ready to play.

And I remember one Fun House ride in particular: the human centrifuge, a huge wooden turntable that hovered just an inch or two above a worn padded floor. I remember how we all scrambled aboard and plastered ourselves to the great polished disk like animated frescoes, chattering in anxious anticipation. I remember the hum as the motor came alive beneath us and the wheel started to turn, slowly at first, then accelerating, faster and faster until those still clinging to it in extremis suddenly flew off in all directions — screaming in delight. And of course, no one got hurt…

Fade out and fade in, now fifty-five years later: Playland at the Beach in San Francisco is gone, long ago demolished and auctioned off, replaced by rows of nondescript seaside condominiums. Some things remain, however: the roar of the Pacific, Ocean Beach, the Great Highway, the fog, the chill, the salt air and, of course, the memories. Fifty-five years later it occurs to me that life in the early 21st-century is very much like the human centrifuge ride of my childhood, very much like the spinning wheel in the Fun House at Playland-at-the-Beach. My human centrifuge, however, runs 24/7, day after day, month after month, year after year. It never stops. It never even slows down. In fact, it accelerates with each revolution. The centrifugal force and inertia we encounter on it continually increase, and there’s no padding to break our fall when we get tossed off; everyone who gets tossed off gets hurt. Welcome to modern life in the Great Age of Mediation.

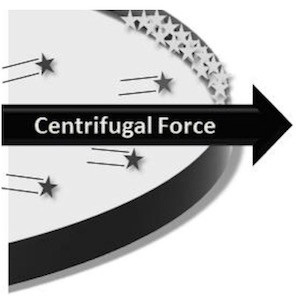

It’s time to introduce you to the Centrifugal Map. A graphic representation follows…

The big black arrows on either side of the Centrifugal Map remind us that the human centrifuge is always spinning, while the thin lines that bisect the wheel horizontally and vertically represent the centrifugal force exerted outward from the center in all directions by the spinning wheel. To properly invoke the human centrifuge as a metaphor for modern life, however, we need to consider three things:

That the wheel always spins and never slows down for anyone. Our job is to withstand the centrifugal force and remain on the wheel at all costs. And if we get tossed off, as sometimes happens, we must climb back on again, irrespective of any injuries or scars we may sustain in the process.

In the absence of countervailing forces or actions, we will always drift by default towards the wheel’s outer edge in the Great Age of Mediation. The centrifugal force generated by the human centrifuge is inexorable, and will always act to nudge us outward towards the edge. It therefore doesn’t matter which way the wheel turns: clockwise, counterclockwise, liberal, conservative, Democrat, Republican, Christian, Muslim, Jew, Buddhist, or Hindu — the physics that govern the wheel are ordained from above, constant and inviolate.

Where we are on the Centrifugal Map at any given point in time will determine the quality of our lives at that moment, and where we spend most of our time on the wheel will determine the general quality of our lives. Albert Einstein once observed that the outer edge of a phonograph record spins faster than the hub at the center. The same is true of the human centrifuge and the Centrifugal Map: in general, life is better towards the center of the wheel where there is less centrifugal force to battle, and worse towards the outer edge where the centrifugal force is greatest. So not only is it important to stay on the wheel, but also to position yourself as close to the center as possible.

The first two conditions above qualify as force majeure, pure acts of God, things over which we exert no control whatsoever — no matter how hard we try. Simply stated, the human centrifuge will always spin, and will always generate centrifugal force outward from the center as a default condition, irrespective of our behavior. Only the third condition — where we position ourselves on the wheel — is subject to our own influence. At any given point in time we are just as likely to find ourselves positioned on the human centrifuge either closer to the center of the wheel or closer to the wheel’s outer edge.

Let’s examine how our position on the wheel affects the quality of our lives, starting from the outer edge then working our way inward. Remember while we do so, however, that our lives are works in progress, and that our position on the human centrifuge and Centrifugal Map can change from day to day, or even from moment to moment, depending on circumstances and the choices we make.

Life on the Edge of the Human Centrifuge…

The Big Lie promoted to us by our meta-addiction to all things media and all things digital in the Great Age of Mediation rightfully interprets our faith as a mortal threat to its own existence, and therefore positions it in our heads as the polar opposite of and primary threat to reason. Portrayed graphically on the Centrifugal Map, the Big Lie looks like this…

In truth, however, reason and faith belong side by side in the center of the Centrifugal Map because faith is a reasonable response to the insanity we encounter in the Great Age of Mediation. Remember, the Big Lie is by definition an extreme position, just as addiction is by definition an extreme condition, and cannot permit any meaningful reconciliation of the two. Such a marriage would threaten to produce a more balanced and moderate lifestyle, something our meta-addiction to all things media and all things digital simply cannot and will not tolerate.

All of us spend time (perhaps more than we’d like) on the outer edge of the human centrifuge. Indeed, life on the edge is the default condition in the Great Age of Mediation simply because addiction is the default condition in the Great Age of Mediation. Addiction aside, however, our paths through life are strewn with the bones and roadside markers of lost loved ones, failed businesses, divorce, unemployment, violence, financial problems and legal hassles. These and other Black Swan events rattle our cages, knock us upside the head and loosen our grip on the wheel. And sometimes — weary from the day-to-day attrition of the battle just to stay on the wheel — we close our eyes to steal a moment or two of blissful quiet, then wake with a start to find ourselves suddenly drifting right back out towards the edge again. Out there, out where the storm winds blow, we have no time to lick our wounds, and simply brace ourselves for the next big gust. But that’s life on the edge in the Great Age of Mediation.

Remember, the quality of life is a function of how and where and with whom we invest our time and faith.

In the Great Age of Mediation, most of our time is spent on the edge of the human centrifuge in default reaction to the pressures and demands — the centrifugal force — encountered in extreme environments.

Little or no time therefore to contemplate right or wrong, little or no time to ponder healthy versus unhealthy or sacred versus profane. All while our super-addiction to all things media and all things digital tells us — as part of the Big Lie — that our utter obsession with all things media all things digital is not only benign, but a legitimate and reasonable response to the extreme environments we encounter in life on the edge in the Great Age of Mediation.

Life of the edge of the human centrifuge is also where we encounter much more inertia in our lives per the following illustration…

The massive inertia generated by our meta-addiction to all things media and all things digital combines with the intense centrifugal force we feel at the edge of the human centrifuge, and together they work to prevent us from moving inward towards the center of the wheel where the quality of life is much better, much more liberated and much less stressful.

Life on the edge of the human centrifuge keeps us mired in the stressful minutiae and technology-driven exigencies of day-to-day survival. It demands that we spend nearly all of our time just fighting to stay on the wheel while we struggle to feed and sustain our obsessions and addictions.

But time and energy devoted to the struggle to feed our obsessions and addictions in life on the edge is time and energy diverted away from and borrowed against the quality of life. And of course we cannot afford to borrow indefinitely; the quality of life — like all credit lines — is finite.

The daily skirmishes and battles with our obsessions and addictions carve the harsh landscape, the rollercoaster ups and downs, of life on the edge in the Great Age of Mediation. The immense struggle to maintain and support our fealty and addiction to media consumes almost all of our waking time. Of course no amount of talent, money, or good will can improve our position on the human centrifuge in the absence of time — because we simply cannot buy, beg, borrow, or steal any more of it. And therein resides the real dilemma:

In the Great Age of Mediation life on the edge seems full of just about everything except time — and peace of mind.

Ironically, life on the edge is where all of our time is consumed in fealty and addiction to our time-saving digital technologies. Ultimately, however, our obsessions with and addictions to the same time-saving digital technologies imprison and enslave us. Life on the edge in the Great Age of Mediation keeps us thoroughly entertained and thoroughly mesmerized by high-definition and surround-sound technologies wherever and whenever we want them, but thoroughly immersed in the glittering gulags of our own obsessions and addictions. Life on the edge keeps us mired in perpetual crisis management. And unfortunately, life on the edge is precisely where we choose to spend more and more of our time in the Great Age of Mediation.

Life in Transition on the Human Centrifuge…

While we have no choice but to remain on the human centrifuge, we are called upon nevertheless to make the daily choices that — in no small measure — determine our position on it. Free will is a muscle we need to exercise. Functionally, the choices we make — minute by minute, hour by hour and day by day — either keep us where we are on the human centrifuge, combine with circumstance to move us closer to the outer edge, or combine with circumstance to move us closer to the center.

Our predisposition to choose in ways that promote either the quality of life or our obsessions and addictions depends largely on where we are positioned on the wheel at the time we make our choices.

Obsessive-compulsive behavior aside, we are very much creatures of habit to begin with, and all behaviors — good, bad, and indifferent — become easier with practice. The closer we are to the outer edge, the more likely we are to predicate our choices on convenience rather than quality, and the more likely we are to slip by default into compulsive behaviors that promote or sustain our obsessions and addictions. Out on the edge we are far more likely to react to our environment, and far more likely to make less-considered and ill-informed choices. The longer we live life on the edge, the more difficult it becomes to imagine any other way to live. Protracted exposure to life on the edge inhibits courageous decisions that will help us escape the prison of our addictive behavior and restore the quality of our lives.

Again, it bears repeating that we are almost always in transition on the human centrifuge, almost always moving farther from or closer to the center. Our movement in either direction almost always results from a confluence of circumstance and the choices we make from moment to moment, day to day. Movement in either direction is no guarantee that we will be moving in the same direction five minutes from now.

The only guarantee is that the quality of life will improve as we move towards the center of the human centrifuge, and will deteriorate as we move towards the edge.

Life in the Center of the Human Centrifuge…

Life in the center of the human centrifuge is a fully liberated and wholly conscious life predicated on the deliberate choice of quality over convenience in an environment less compelled and controlled by our obsessions and addictions. Although life in the center of the human centrifuge is antidotal to life on the edge, they are not polar opposites. Indeed, there’s nothing whatsoever polar about the quality of life at the center of the human centrifuge. It will always meet you halfway.

Life in the center of the human centrifuge is a conscious balance of faith and reason restored in proportion.

In fact, the center of the human centrifuge is where we begin our journey in life, born free with free will, and where freedom and free will remain as essential life forces throughout our lives.

The table below summarizes the contrasting lifestyle attributes that characterize life on the edge of the human centrifuge versus life in the center…

Take a moment to review the above table once again, then ask yourself: If the quality of my life is a function of how and where and with whom I invest my time and faith, how and where and with whom would I rather invest them?